By Dennis Wilson

High winds, snow, ice, extreme cold: Today we have the means to moderate these curses of wintertime, but things were different in the “good old days.” Farm families spread across the vast American landscape knew the meaning of the word “snowbound,” and the struggles that term implied. We get blizzard warnings from The National Weather Service created by using supercomputers and satellites. The television weatherman gives us the definition of a blizzard: “sustained winds of at least 35 mph lasting for a prolonged period of time— typically three hours or more. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling but loose snow on the ground is lifted and blown by strong winds.” We settle in, turn up the gas furnace, flip on the television, and wait the weather out in comfort. Even those who must travel turn on the heater and the stereo, and drive in front wheel or four wheel drive vehicles on a modern highway usually cleared by large, powerful snowplows. It wasn’t that way in the past. People experienced the full force of nature.

By 1870 Wisconsin’s population had grown to 1,054,670. Three quarters of its citizens lived on farms or in cities with a population of under 2,500. In the 1870’s and 1880’s winters were often extremely harsh. The “Little Ice Age” which had persisted from about the year 1300 was coming to an end. The winters in the years before the 20th century were characteristically colder and longer.

Those who were subjected to blizzards and arctic cold waves had to be prepared. They could not depend on supplies from outside. Supplies came by animal drawn wagons and sleighs, or by rail. Harry Barnett recalled that during the hard winter of 1881 no trains could reach Lancaster due to the snow pack from January 23rd through April 11th, and then they got only as far as Liberty.

In her book “The Long Winter” Laura Ingalls Wilder described the struggle to survive in South Dakota in the winter of 1880-81. Her book describes a life threatening expedition mounted to get out and return with supplies after the Railroad suspended its operations in the Dakotas. There were no government emergency services, no helicopters to drop food or fuel, no emergency shelters, no GPS, no telephones, no reliable weather forecasts, and no powerful road plows. We would hardly call what they had roads. Even mighty steam locomotives were trapped in the snow that filled the railroad cuts. There were few packaged foods, so starvation threatened those who were isolated and hadn’t stocked up or harvested and stored enough food. People in tar paper covered wood frame homes froze to death as the wind ripped away the covering, or starving animals tried to eat it, defeating all their attempts to keep warm. The log cabin or sod house was much better shelter in a blizzard, as long as its roof was sturdy, for very often the blizzard demolished roofs and swept them into the white emptiness, leaving those below to die.

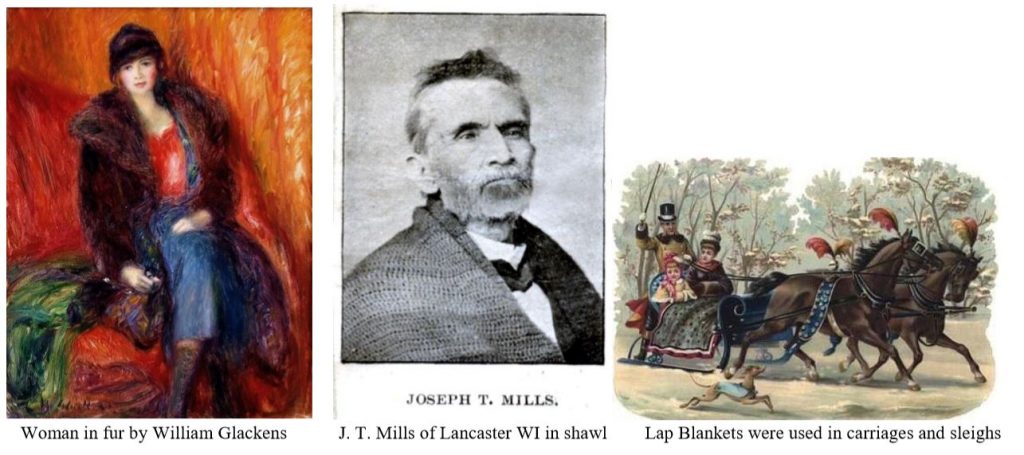

The early settlers of Wisconsin faced these same challenges. It is interesting to look at old photographs of people in wintertime. In many of those you will note that they seem very inadequately dressed for cold weather. Men wear light jackets and hats that do not cover the ears. A significant number wear no boots. There were heavy coats available such as these 19th Century examples:

In those days heavy blankets, scarves and shawls supplemented sometimes meager outerwear. Against the force of a bad winter storm all were inadequate for extended exposure. Wisconsin is known as a cold place in the winter. The state record low is 55 degrees below zero

Fahrenheit set in Couderay, Wisconsin in 1996. In 1983 Couderay hit 53 below. In the winter of 1929 dozens of Native Americans died of exposure and pneumonia at the same place. In Grant County the coldest stretch of weather occurred between February 7th and the 12th of 1899. In Lancaster, the average daily high temperature was -5.7 degrees. The average low was -24.7 degrees.

The stories of Wisconsin are full of accounts of vicious blizzards and cold spells. Here are a few examples:

From February 8-10, 1936 a blizzard, following on the heels of a snowstorm the previous week struck the entire State of Wisconsin. Heavy snow, temperatures in the double digits below zero and strong winds caused severe drifting. Roads in Grant and Iowa counties were impassable with drifts of 10 – 12 feet. On Saturday, February 8th, 61 year old Ben Benson of Boscobel, who worked at the railroad depot, disappeared as the Storm was building. On Monday the 10th his frozen body was found in a snow drift half a block from his home. In Chicago on the Monday after the blizzard, while temperatures in the upper Midwest ran in the 20’s below zero, it was reported that milk supplies were down 40 percent. No deliveries had reached Chicago from Wisconsin since the previous Friday, the day before the storm began. Farmers were storing their milk anywhere they could. In Walworth County, 21 year old Farmhand Eddie Delano was helping to push a truck from a snowbank. First his nostrils froze shut. Then unbelievably, his lips froze together and he began to suffocate. He was taken into a heated truck cab but it was apparent that the warmth would not take effect in time to save him. A man ripped his lips apart. “The flesh was torn badly” The Milwaukee Journal reported in its article which bore the headline “Rough First Aid.”

While the blizzard was raging in Wisconsin a “Black Blizzard”, a massive dust storm was choking Colorado and five other states. Along Wisconsin’s main highways farmers were taking in drivers stranded in the snow drifts. Local taverns and Inns were packed to overflowing. Some rural farm homes sheltered up to 25 travelers, trying to make the food and beds suffice. Things were serious in towns and villages also. Livingston, Wisconsin faced what the Milwaukee Journal called a “coal and water famine.” With no train service for over a week, supplies of coal, the most widely used fuel of the day were going fast, and dealers limited sales. Most of the water pumps in town were frozen, and the fire department reservoir had less than a foot of water to meet the possibility of fire in the raging winds. Crews were working all over the state to clear snowbound rails and free stranded trains. In Jackson, Wisconsin 89 passengers were stuck in 18 foot snow drifts with no heat or food for two days

Some of the worst storms are those that strike early or late in the winter season. Blizzards that scour the state also thrash the great lakes. The Great Lakes are the most dangerous navigable waters on earth, and Lake Michigan is the worst in terms of sinkings and lives lost. The numbers for the Lakes are chilling. Between 1878 and 1897 6,000 ships were wrecked or sunk. In the following century disasters continued in the turbulent lakes. In November of 1913 the Great Lakes were struck by an early blizzard, sometimes called on the lakes a “extratropical blizzard” or “November Witch.” Waves of over 35 feet driven by 90 mph winds battered the hapless vessels on the water. 250 lives were lost as 19 ships sunk and 19 more were stranded. It has gone down in history as the “White Hurricane.” Great Lakes ships have continued to go down in November storms. Gordon Lightfoot memorialized the sinking and loss of the entire crew of the Edmund Fitzgerald on November 10, 1975 on Lake Superior.

Extreme temperature drops often characterize the most severe storms. The Armistice Day Blizzard, which struck the Midwest on November 11, 1940 was such a storm. Armistice Day, now called Veterans Day saw very mild conditions. Early afternoon temperatures were in the 60’s. Many hunters took a day off work and went to the waters of the Mississippi to take advantage of the perfect Duck Hunting conditions. Many did not take cold weather outfits. Conditions deteriorated rapidly. The temperature dropped as much as 50 degrees in minutes, 50 mile per hour winds assailed the unprepared. That evening and into the next day sleet and then up to 27 inches of snow fell, drifts formed. Boats on the river were swamped and men drowned. Others were stranded on islands. Many who got to shore were unable to get their vehicles out. Some took shelter under overturned boats. The result was that many froze to death. The official death toll from the storm was 145, which included 66 sailors on the Great Lakes. 13 died in Wisconsin.

An engineer at the University of Wisconsin at Platteville recalled being called to work to get the university radio station on the air. “My supervisor,” he wrote “told me that there were no radio stations on the air in the whole Southwest corner of the state.” The university station had an emergency generator. He wrote:

“During the early hours we carried emergency messages for the local police and sheriff’s offices. The local commercial radio station in Platteville did not have power, so I called their news director and asked him if he wanted to get his super Rolodex and come over to the University and give us a hand. He appeared almost immediately. For the next two days the University radio station was the only one on the air. The students really got a lesson on the Broadcasting Industry and emergencies.”

Farmers had to try milking their cows by hand if they had no emergency generators. Volunteers took water to farmers who could not pump it for the livestock. A man recalled the storms effect on his family’s farm: “For a while it seemed like an adventure, until we kids realized that our well had an electric pump, and water was about to get scarce. I can still remember how my mother went off when one of us flushed a toilet by force of habit at some point on Thursday evening. That, and the sound of the wind howling around the dark, cold farmhouse.” He reported that it wasn’t much better in Madison:

Two of the city’s commercial TV stations, WISC and WKOW, were off the air. At WMTV, which was apparently still on the air (the story in the paper wasn’t clear), ice was the major problem, falling from the transmitter tower and smashing through the roof of the station’s administrative offices, which were not in the concrete-reinforced part of the station building. Employees were told to wear hard-hats outside the building. Madison’s cable system struggled with outages as well.

There are always those who revel in the hardship and primitive conditions that winter storms and other natural disasters visit upon us in Wisconsin. So what if ravenous dogs unable to find food in the blizzard were attacking cows. Men of an earlier time and a tougher nature could have handled that and so could we. Who needs roads and rails? If we were cut off from the rest of the world fuel could be supplied by chopping wood. We can produce our own food and milk, and barter with our neighbors wrote the Grant County Herald’s editor: “Give a family potatoes , cabbage and onions, with a quarter of beef or a side of pork, flour, beans and apples and they would get along and probably be all the better of the simple fare. Life would tone down and become more rational. At the end people would say they enjoyed the experience and it would be something to talk about for years to come.”

The one benefit I can find in these harrowing stories of yore is that doctors actually came to you when you were sick! There are numerous stories of hardy doctors braving the deadly blizzard to go to a suffering child. Such stories did not always turn out well for the doctors. In February of 1938 the front page of the Grant County Herald carried the sad news of the passing of Dr. T. E. Farrell, age 60, of Seneca. The good doctor, it was reported, died at his post of duty caring for a sick child 14 miles from town. He had “shoveled his way through drifts and walked a mile carrying his kit in order to reach the patient.” The exertion caused his heart to fail. With today’s advances in medicine that would not happen. The patient would suffer heart failure trying to get to the doctor.